Salts and Peppers

Table of Contents

Goal

We are going to take a deep dive into salts and peppers and, specifically, their use for safely storing passwords in a username/password authentication system.

Authentication Overview

Authentication is a way to prove who you are. This can be done in several ways:

- By revealing what you know (Knowledge-based):

- Username/password

- PIN

- Security questions

- By revealing what you hold (Possession-based):

- Physical items

- Security token

- Mobile phone (identified using unique attributes like IMEI number)

- Passport or Driver’s License (or other physical ID cards)

- Digital items

- Authenticator app

- One-Time-Password (OTP) delivered via

- SIM card

- via an SMS

- via a Voice Call

- Physical or Digital items

- Digital Certificate

- QR Code

- Physical items

- By revealing what you are (Inherence-based):

- Fingerprints or Hand Geometry

- Voiceprint

- Face recognition

- Retina or Iris scan

- Behaviour (like typing rhythm)

- By revealing where you are (Location-based):

- GPRS location

- Wi-Fi router location

- IP address geolocation

Authentication can be achieved using one or more of the mechanisms. Depending on the application, the authentication system may choose to use more than one authentication category. This is called two factor authentication (2FA). It is less convenient for the user but adds more security.

A username/password authentication system is a knowledge-based system. We are going to only look at this mechanism as it is simple and convenient, and doesn’t require any additional hardware. It is also very secure if implemented correctly by understanding the recommendations in this article.

Password Human Factors

Human Memory

Generally people can remember at most 4-5 distinct passwords (Users are Not the Enemy, 1999, page 46) yet are likely members of dozens of digital services that require username/password authentication. For this reason they are likely to use the same passwords more than once, or variations of them, for different services. This means if a password is stolen it potentially has larger security implications than for just that one service. By applying the practises in this article it will be virtually impossible for one of these passwords to be obtained through one of the most common security breaches: a data breach. For examples of recent data breaches, and their extents, see the ’;–have i been pwned? website.

Memory limitations can be overcome by writing down passwords or by using a password manager. Writing down, or otherwise recording passwords, is not secure in that people may find your paper or find your electronic copy of your password. Using a password manager runs the risk of the manager being compromised and all your passwords being discovered. So in this article we will focus only on username/password authentication and how salts and peppers relate to it.

Typeability

People must be able to type their passwords on their own devices and also other people’s devices (in the case that they are away from their own devices or have lost one of more of their devices). For this reason we will focus on the 95 ASCII visible, typeable characters for password calculations in this article. This includes both the upper and lower case latin alphabet letters (26×2), the numerals (10) and special characters (33) including the space character.

| Count | ASCII Code (Decimal) | ASCII Character |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | space |

| 2 | 33 | ! |

| 3 | 34 | ” |

| 4 | 35 | # |

| 5 | 36 | $ |

| 6 | 37 | % |

| 7 | 38 | & |

| 8 | 39 | ” |

| 9 | 40 | ( |

| 10 | 41 | ) |

| 11 | 42 | * |

| 12 | 43 | + |

| 13 | 44 | , |

| 14 | 45 | - |

| 15 | 46 | . |

| 16 | 47 | / |

| 17 | 58 | : |

| 18 | 59 | ; |

| 19 | 60 | < |

| 20 | 61 | = |

| 21 | 62 | > |

| 22 | 63 | ? |

| 23 | 64 | @ |

| 24 | 91 | [ |

| 25 | 92 | \ |

| 26 | 93 | ] |

| 27 | 94 | ^ |

| 28 | 95 | _ |

| 29 | 96 | ` |

| 30 | 123 | { |

| 31 | 124 | | |

| 32 | 125 | } |

| 33 | 126 | ~ |

This gives a total of 26x2 + 10 + 33 = 95 characters.

Emojis & International Characters

Users who want to use international characters or emojis in their passwords can if their authentication system allows it. Emojis in passwords can be easier to remember and add to password entropy (UK firm [Intelligent Environments] launches emoji alternative to Pin codes, 2015). Modern web based applications support Unicode characters by default which include 3664 standardised emojis (as of Unicode 15.0, August 2023).

International character and emoji use increase password security in that an attacker will need to include them in their attack dictionary, requiring a significantly larger attack dictionary.

Users must be aware that they may have difficulty typing emoji or international character passwords on devices other than their own. The universality, standardisation and typeability of emojis has come far but should still be considered as a factor when creating passwords containing them.

What are Salts & Peppers?

A salt is a random value added as additional input to a password hash function to protect the resulting hash from reverse hash lookups (and optimised versions of reverse hash lookups such as rainbow tables).

A pepper is a random value added as additional input to a password hash function to protect the resulting hash from dictionary and brute force attacks.

Salts are stored in the user table in the database, one random salt per user, whereas a pepper is a single random value specific to an application and is stored outside of the database (preferably in some form of secure storage). This way if the system is attacked and the database is breached (e.g. through direct access or SQL injection attacks) the pepper would need to be compromised separately since both live in their own security enclaves.

Storing Passwords

Consider a typical application that stores usernames and passwords. The naive strategy would be to store the usernames and passwords in a database without encryption:

| Username | Password |

|---|---|

| user1 | qwerty |

| user2 | 12345678 |

| … | … |

If the database is compromised by an external hacker or rouge employee the usernames and passwords are directly exposed and can be used to login to any user’s account through the application’s login user interface.

Password Hashing

A better strategy is to store the hash of the password. A hash is the output of a hash function. A hash function is a one-way cryptographic function that produce a seemingly random output that aims to be unique per input. Once hashed, the password hash cannot be unhashed (unless there is a weakness in the hashing algorithm used). Thus a password hash is ideal for use in storing obscured passwords.

HashedPassword = SHA256(Password)

| Username | HashedPassword |

|---|---|

| user1 | 65e84be33532fb784c48129675f9eff3a682b27168c0ea744b2cf58ee02337c5 |

| user2 | ef797c8118f02dfb649607dd5d3f8c7623048c9c063d532cc95c5ed7a898a64f |

| … | … |

In this article we are using the SHA256 hash function for simplicity. Do not use SHA256 password hashing in a production environment because if the database and the pepper have been compromised, weaker passwords will be easy to crack through dictionary or brute force attacks. SHA256 is a fast hashing algorithm that is designed to generate hashes very quickly. This aids dictionary and brute force attacks which need to perform hash calculations as fast as possible.

Use Argon2 or a similar slow hash function instead which will provide effective resistance against these attacks. See my article on Hash Algorithms for more details about various hash functions and their characteristics.

Note: People often talk of passwords being encrypted. Technically passwords should hashed, not encrypted. Encryption is a two-way cryptographic process. This means the original password can be recovered from the encrypted password if the encryption key is known. Recovery of the original password is not needed for password storage and just adds additional attack vectors to an authentication system.

Reverse Hash Lookups

Since cryptographic hash functions are designed to be irreversible you might think that passwords are now safe in the database, even if it is compromised. If all password where strong (e.g. 10+ random characters) and a slow hash function, such as a well configured Argon2, was used then this would be the case. The reality is that users often choose very weak passwords such as the ones I chose: qwerty and 12345678. What an attacker can do is prepare a table of common passwords and their corresponding hashes. This is known as a reverse hash lookup table. A specific password hash can be rapidly searched for in the table and the corresponding unhashed password extracted.

| HashedPassword | Password |

|---|---|

| 65e84be33532fb784c48129675f9eff3a682b27168c0ea744b2cf58ee02337c5 | qwerty |

| ef797c8118f02dfb649607dd5d3f8c7623048c9c063d532cc95c5ed7a898a64f | 12345678 |

| … | … |

Reverse hash lookup tables are most useful against slow hashing algorithms since the hash computation time will be large compared with minimal storage space required to store the hash result. For fast hashing algorithms like SHA256 the gains, if any, will be significantly less.

Rainbow Tables

The reverse hash lookup process can be optimised by using a technique known as rainbow tables. It can make the lookup tables orders of magnitude smaller with just a slight slowdown in lookup speed.

Further reading:

- [Making a Faster Cryptanalytic Time-Memory Trade-Of, Philippe Oechslin, 2003], https://lasecwww.epfl.ch/pub/lasec/doc/Oech03.pdf

- Rainbow Tables (probably) aren’t what you think — Part 1: Precomputed Hash Chains, Ryan Sheasby, 2021, https://rsheasby.medium.com/rainbow-tables-probably-arent-what-you-think-30f8a61ba6a5

Salts

Salts, like peppers, are combined with passwords before hashing, adding to the password hash’s security. Salts are different to peppers in that they are intended to be unique per user and are stored in the database alongside the username. Salts increase the storage space required for reverse hash lookup tables in proportion to the number of unique salts used. They can render reverse hash lookup tables useless since a new table needs to be created for each unique salt. Without being able to reuse the tables their use only adds overhead to password cracking attempts.

HashedPassword = SHA256(Password + Salt)

| Username | Salt | HashedPassword |

|---|---|---|

| user1 | 3299942662eb7925245e6b16a1fb8db4 | 5f9eb7a905e2159f2bcde6414020e03815dc7fd4655841d36d34be091a009d30 |

| user2 | d346a4fa7f9fd6e26efb8e400dd4f3ac | 5631c77a32ec3282bca6c8291f87409b0b5f9442bec280d283efe4e6e976e370 |

| … | … | … |

Username or Email as Salt

One might think that you could use the username or email address of a user as the salt to ensure uniqueness. While this initially seems a great idea you would not be able to change the username or email address without also creating a new password. Let’s look at some other strategies then.

Sequential Salts

We could use a sequence number as a simple way to ensure unique salts. The vulnerability this approach has is that the attacker can predict the salts beforehand and create a reverse hash lookup of known salts (e.g. 1 to 1000) combined with likely passwords. This is the same vulnerabilities that short salts have.

The vulnerability can be mitigated by combining a long random pepper (64 or more bits) with the salt sequence number. Any reverse hash lookup tables now cannot be reused on other deployments regardless of if the pepper is known or not: different peppers make the reverse hash lookups span a different range of values.

Short Salts

If a salt is too short an attacker may create reverse hash lookup tables containing every possible salt combined with likely passwords. Using a long salt (64 or more bits) ensures these tables would be impossibly large. Another solution is to use a pepper in combination with short salts as also suggested with sequential salts above.

Salt Length

The salt needs to be long enough that it is not worth it for an attacker to undertake rainbow table attacks. For simplicity during these calculations let’s assume a maximum expected userbase of 8 billion users (about the number of people on planet Earth as of 2023).

Salt Collisions

If the salt length is short there will be salt collisions i.e. duplicate salts. The attacker can use their rainbow table on all password hashes that have the same salt. In the case of a 16 bit salt, a single rainbow table would be able to crack 122 070.31 password hashes on average given 8 billion users

8 000 000 000 / 232 = 122 070.31

Using the table below we can see that we should choose a salt of 32 bits or more to avoid excessive collisions. A collision rate of 1.86 means a generated rainbow table can be used to crack 1.86 password hashes on average which would be barely worth generating for the attacker.

Salt Bits |

Unique Salts (2Salt Bits) |

Average Collisions per Salt (8 billion users / Unique Salts) |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | 65 536 | 122 070 |

| 32 | 4 294 967 296 | 1.86 |

| 64 | 1.84 × 1019 | 4.34 × 10-10 |

| 96 | 7.92 × 1028 | 1.01 × 10-19 |

| 128 | 3.40 × 1038 | 2.35 × 10-29 |

| 256 | 1.16 × 1077 | 6.91 × 10-68 |

Rainbow Table Storage

Let’s start with a table of SI units used for storage. This will make it easier to visualise the quantities we are about to discuss:

| Unit | Bytes |

|---|---|

| Kilobyte (KB) | 1 000 |

| Megabyte (MB) | 1 000 000 |

| Gigabyte (GB) | 1 000 000 000 |

| Terabyte (TB) | 1 000 000 000 000 |

| Petabyte (PB) | 1 000 000 000 000 000 |

| Exabyte (EX) | 1 000 000 000 000 000 000 |

| Zettabyte (ZB) | 1 000 000 000 000 000 000 000 |

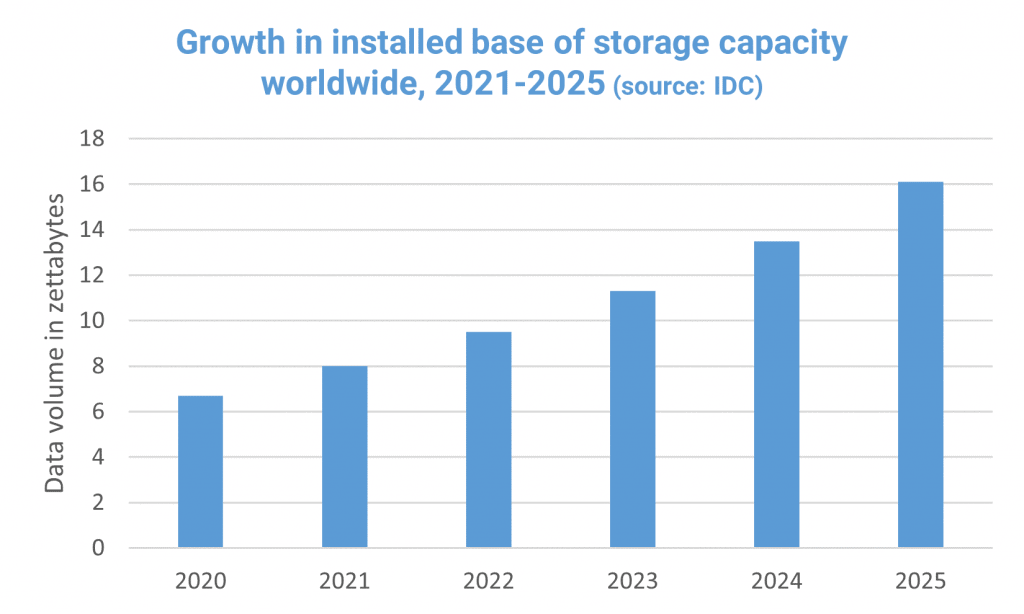

From the figure below we can see that global data storage is predicted to be 16 ZB by 2025 and is doubling every 4 years. A formula to predict the storage available at a given year is thus 16 × 2(year - 2025)/4 ZB. To be safe we want to force our attackers’ rainbow tables to be larger this value for some years into the future so that there is no chance of a rainbow table attack.

For reference, readily available public unsalted rainbow tables commonly vary from hundreds of MBs to TBs in size. Let’s consider an extreme case where a rainbow table is only 1 MB in size. Salting forces the number of rainbow tables needed by an attacker to be equal to the number of unique salts. So we get:

Salt Bits |

Size of all Rainbow Tables in ZB (Unique Salts × 1 MB) |

Unique Salts |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.000000000065536 | 65 536 |

| 32 | 0.00000429 | 4 294 967 296 |

| 64 | 18 446 | 18 446 744 073 709 551 616 |

| 96 | 79 228 162 514 264 | 79 228 162 514 264 337 593 543 950 336 |

| 128 | 340 282 366 920 938 463 463 374 | 340 282 366 920 938 463 463 374 607 431 768 211 456 |

| 256 | 115 792 089 237 316 195 423 570 985 008 687 907 853 269 984 665 640 564 039 457 584 | 115 792 089 237 316 195 423 570 985 008 687 907 853 269 984 665 640 564 039 457 584 007 913 129 639 936 |

From the table above we can see that increases in the bits of salt used exponentially increases the minimum storage required for the rainbow tables, and global storage increases at a relatively slower pace over time.

Let’s graph the global storage projection over a longer period of time and see how many bits of salt we need to cover those values.

From the graph above and the table below we can see that 64 bits of salt would be more than sufficient in all present day cases and decades into the future at the current data storage growth rate:

| Salt Bits | Estimated Minimum Years of Protection |

|---|---|

| 64 | 41 |

| 96 | 161 |

| 128 | 296 |

| 256 | 808 |

For reference we show here a couple of other recommendations for salt lengths. We feel these recommendations are somewhat arbitrary since there is no indication how they were derived:

-

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) recommends at least 32 bits in its Digital Identity Guidelines (SP 800-63B)

-

The Open Web Application Security Project (OWASP) recommends using salts that are 256 to 512 bits long

Pepper

A pepper is a single, fixed, random value stored separately from the database (preferably in some form of secure storage). An attacker may compromise the database and steal the data there, but without the pepper they will have to spend brute force effort to find a password and the pepper’s value. If the pepper is sufficiently strong then it will be impossible to brute force.

The pepper is combined with the password to produce different hash values compared with the an unpeppered user table. We see that the reverse hash lookup table we created before will no longer be applicable to our newly peppered passwords above as the SHA256 values do not match any more:

PEPPER = wtWy8vb3Ov4FFiFF

HashedPassword = SHA256(Password + PEPPER)

| Username | HashedPassword |

|---|---|

| user1 | 2583015da33f1fd72efc0b6384412a9d5443a55f52284fa1f7e0f9b5ebe3f38d |

| user2 | 51d437a138ac402cba22c12349b874259eecd38087728f961e10260308d4ead7 |

| … | … |

Pepper Bits

For simplicity let’s first look at SHA256 password hashes and how much effort would be required to discover an arbitrary password hash’s pepper, given we have the password hash and its salt. Remember that SHA256 is a fast hashing algorithm, so it will give worst-case results in terms of the effort required. A slow hashing algorithm will require orders of magnitude more effort.

Again, to start with, let’s reference a table of SI units denoting hash rates. This will make it easier to visualise the quantities we are about to discuss:

| Units | Hashes per Second |

|---|---|

| KiloHashes/s (KH/s) | 1 000 H/s |

| MegaHashes/s (MH/s) | 1 000 000 H/s |

| GigaHashes/s (GH/s) | 1 000 000 000 H/s |

| TeraHashes/s (TH/s) | 1 000 000 000 000 H/s |

| PetaHashes/s (PH/s) | 1 000 000 000 000 000 H/s |

| ExaHashes/s (EH/s) | 1 000 000 000 000 000 000 H/s |

The most powerful network of computers able to produce SHA256 hashes in 2023 is the Bitcoin network. Since Bitcoin has, by many order of magnitude, the most dominant SHA256 hash rate, at 440 EH/s as of April 2023 (the next being Litecoin at 920 TH/s), we can safely use this as a basis for our calculations. It also has readily available public statistics on its hash rate over time.

| Date | Bitcoin Hash Rate (EH/s) | Days until Doubling |

|---|---|---|

| May 2023 | 380 | |

| Jan 2022 | 190 | 490 |

| Sep 2019 | 93 | 850 |

| Apr 2019 | 46 | 150 |

| Feb 2018 | 23 | 420 |

| Dec 2017 | 11 | 62 |

| Aug 2017 | 5.8 | 120 |

| Jan 2017 | 2.9 | 210 |

| Jun 2016 | 1.4 | 210 |

| Dec 2015 | 0.73 | 180 |

| Aug 2015 | 0.37 | 120 |

| Aug 2014 | 0.18 | 370 |

| Jun 2014 | 0.09 | 61 |

In order to brute force the salted and peppered password hash we will need to try, on average, half of all the possible pepper values in order to obtain the actual pepper.

Let’s take the worst case of the most acceleration of the Bitcoin hash rate: doubling every 60 days. Then we can set a maximum hash rate using the formula:

Bitcoin hash rate maximum = 380 × 2(days past May 2023 / 60) EH/s

hashes = 2pepper bits

| Years into the Future | Bitcoin Hash Rate |

|---|---|

| 0 Years | 3.80 × 102 EH/s |

| 1 Years | 2.43 × 104 EH/s |

| 10 Years | 4.38 × 1020 EH/s |

| 100 Years | 4.04 × 10185 EH/s |

| 1 000 Years | 8.90 × 101 834 EH/s |

| 10 000 Years | 6.04 × 1018 327 EH/s |

| 100 000 Years | 3.89 × 10183 254 EH/s |

| 1 000 000 Years | 4.77 × 101 832 522 EH/s |

If we are using all the world’s Bitcoin hash power to crack a peppered password, we can see from the chart that from 94 bits onwards the brute force will take more than a year to complete. Since a long pepper does not take any significant extra storage or computational power you can choose at least 128 bits which will take over 20 000 000 000 years to crack.

Risks

This method is secure if the pepper is kept secret. But if the pepper is discovered the attacker can easily make a reverse hash lookup table with the pepper in appended to each password and use this to attack the peppered user table.

If the pepper is lost (or is changed) users will have to create new passwords to create newly peppered password hashes.

Node.js Pepper Implementation

In a Node.js implementation we would commonly store the pepper in a .env file that can be accessed by the dotenv package. For security reasons (especially if using a public code repo) make sure you remove the .env file from your version control system by modifying your .gitignore file to include:

.gitignore

.env

Add the pepper value to the .env file:

.env

PEPPER=wtWy8vb3Ov4FFiFF

Now you can read the pepper from your Node.js code:

app.mjs

import dotenv from 'dotenv'

dotenv.config()

console.log(process.env.PEPPER)

Password Hash Length

Password Hash Attacks

In the case of a database breach, password hashes are susceptible to brute force reverse hash lookup attacks. These are the different types of brute force reverse hash lookups we need to consider:

- Brute force reverse hash lookup

- Dictionary reverse hash lookup

- Precomputed

- Rainbow table

- Realtime

- Precomputed

- Precomputed

- Rainbow table

- Realtime

- Dictionary reverse hash lookup

Fortunately the implementation of a hidden pepper can eliminate all brute force attacks.

Let’s go further and consider the worst case data breach where the pepper is discovered (as well as the database being breached). In this case, salts can protect against precomputed brute force and precomputed dictionary attacks.

The remaining attacks to be dealt with now are realtime dictionary and realtime brute force attacks. ???. The use of a slow hashing algorithm. Weak passwords. Estimate of time taken to crack one password. ???

The simplest brute force reverse attacks hash all possible combinations of passwords and check to see if the resultant hashes exist in the user table. If a match is found then the unhashed password is known.

A brute force attack will discover any password whereas a dictionary attack will only discover a portion of passwords that is determined by the match between the users’ password and the attack dictionary entries. A brute force attack is thus more likely to be used to target an individual user whereas a dictionary attack will obtain a large number of passwords quickly but will only reveal a certain percentage of them (the weaker ones).

If the user table that contains the password hashes and salts is obtained and the pepper is discovered, then an attacker can start using dictionary and brute force attacks on the password hashes. The time it takes to crack them will depend on the password hash length, the hashing algorithm and the hashing algorithm’s parameters. By analysing the two types of attack we can quantitatively determine the number of bits needed for the password hashes.

With Argon2, the slowest algorithm we have considered, hashes can be created in the order of thousands per second with today’s consumer grade hardware. This means that weak passwords could still be cracked, so the use of a pepper is recommended. Dictionary and Brute force attacks can be prevented by using a long random pepper. This is secure even when the database has been compromised but the pepper is still hidden.

The other option is forcing users to choose strong passwords. This will make it difficult or impossible for them to be cracked but also opens other security issues as strong passwords cannot be easily memorized by users. So the user needs to store them in a password manager, on paper or electronically. This comes with its own risks and if we can solve the problem without resorting to strong passwords it will be better for the users and will also result in less customer support requests for us.

Biometric data or QR codes can be used to overcome the problem of forgetting strong passwords but they incur their own sets of security risks. Biometric data needs to be stored securely since its value never changes and additionally it needs to secure the user’s privacy. With QR codes, a device could be hacked and the QR code stolen.

Dictionary Attacks

Dictionary attacks attack weak passwords. Weak passwords are passwords that are short and/or easy-to-guess passwords. The attacker will use a dictionary of common passwords and hash each of them along with the known salt for that user and the application’s pepper. Each resulting hash will be compared to the user’s password hash from the user table. If a match is found then the attacker has just found the user’s unhashed password.

The attack success rate and number of attacks required to find the password will depend on the quality of the attacker’s dictionary and its match with the set of passwords being attacked. Password attack dictionaries can contain complex passwords that contain words from various languages that are mixed with combinations of numbers and symbols. These dictionaries can crack up to around 20% of an average users’ passwords from a list of over a trillion passwords. It is recommended that your application checks new passwords against such a dictionary and warn the user that they are using a weak password if it is in the list.

In terms of the speed of the attack a dictionary attack may be successful with a fast hashing algorithm like SHA256. A single dedicated consumer SHA256 ASIC cryptocurrency mining rig can, as of May 2023, do more than 100 TH/s. This means that more than 100 passwords could be attacked per second (with up to 20% success rate). Thus it’s recommended to use a slow, configurable, hashing algorithm like Argon2 that is orders of magnitude slower when computing a password’s hash. It is unlikely that your application will have lots of simultaneous sign ups or password changes which means that you should configure your Argon2 parameters so that the hashes take around a second to complete. This is short enough that the user will not be too disturbed by the delay computing it, but long enough to provide good brute force resistance. Set the memory complexity as high as your computer can handle since this will provide maximum GPU resistance, making it harder for attackers. Your attacker may have a faster computer than you, so let’s say your Argon2 hash takes 1 second, the attacker may be able to perform the same hash 10x faster. So each brute force attack will take around .1s × 1 000 000 000 / 2 = 50 000 000s = 578 days to complete (with up to 20% success rate). This is very good security considering your system has been completely compromised.

Brute Force Attacks

Brute force attacks attack short passwords by trying every combination of characters for the password, starting from the shortest and moving up to longer ones. The number of attempts required to crack a password via brute force is directly proportional to the number of unhashed password character combinations.

The number of unhashed password character combinations will be set by the application’s UI and the user will be notified of this when creating their password e.g. “8 characters minimum with at least one capital letter, one lowercase letter, one number and one special character”. The application developer needs to balance the password length and complexity requirements with the user’s ability to memorise the password. Longer, more complex passwords are more secure against brute force attacks but are difficult to memorise. If the password requirements are too complex the user will be incentivised to write down the password or store it electronically which makes the password less secure again.

The unhashed password complexity dictates the number of brute force attempts required to crack the password.

Password Hash Length

Humans are not the best at creating or remembering random data. This means human generated passwords are not entirely random. Technically we can say the entropy is lower than truly random data.

The calculations for determining password hash length are similar to that for the salt length. This is because a good hash function will distribute users’ passwords randomly into password hash values, so we can consider password hashes to be random values as we did with salt values.

The difference with Studies show that there are common passwords that are used by a large proportion of users:

Just over 10% of people use at least one of the 25 worst passwords on this year’s list, with nearly 4% of people using the worst password, 123456. - Announcing our Worst Passwords of 2016, SplashData, 2016

If many users are using the same passwords it actually means our password hash can be smaller since the input entropy is lower. We can safely discount this effect so our resultant calculation will be on the cautious side of having a slightly larger and harder to crack password hash than necessary.

The number of bits in a password hash alters the number of password hash collisions that will be experienced. The number of password hash collisions will be given by number of unique passwords / 2password hash bits. Given an upper limit of 8 billion users, 8 000 000 000 / 232 ≈ 1.86

Password Hash Bits |

Unique Password Hashes (2Salt Bits) |

Average Collisions per Password Hash (8 billion users / Unique Salts) |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | 65 536 | 122 070 |

| 32 | 4 294 967 296 | 1.86 |

| 64 | 1.84 × 1019 | 4.34 × 10-10 |

| 96 | 7.92 × 1028 | 1.01 × 10-19 |

| 128 | 3.40 × 1038 | 2.35 × 10-29 |

| 256 | 1.16 × 1077 | 6.91 × 10-68 |

So a

Node.js Username/Password Authentication Implementation

Here is an implementation of a web based authentication system that uses Express.js and SQLite. It implements Argon2 hashing with unique salts per user and a pepper as recommended in this article. It uses the argon2 npm library’s default parameters which are:

import express from 'express'

import betterSqlite3 from 'better-sqlite3'// install issues? try https://github.com/WiseLibs/better-sqlite3/issues/866#issuecomment-1457993288

import argon2 from 'argon2'// install issues? try "npm i argon2; npx @mapbox/node-pre-gyp rebuild -C ./node_modules/argon2"

import dotenv from 'dotenv';dotenv.config()

// Init express

const app = express()

app.use(express.urlencoded({extended:false}))

// Init database

const db = betterSqlite3('users.db')

db.exec('CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS users (username TEXT UNIQUE, password TEXT)')

// Show login page

app.get('/', (req, res) => {

res.send(`

<h1>Login</h1>

<form action="login" method="post">

<label>Username <input name="u" /></label>

<label>Password <input name="p" type="password" /></label>

<input type="submit" />

</form>

`)

})

// Process login form

app.post('/login', async (req, res) => {

const { u, p } = req.body // username, password

const savedPassword = db.prepare(

'SELECT password FROM users WHERE (username=?)'

).get(u)?.password

if (savedPassword && await argon2.verify(savedPassword, p + process.env.PEPPER)) { // ???

res.send('Login Success')

} else {

res.status(401).send('Login Failure')

}

})

// Show registration page

app.get('/register', (req, res) => {

res.send(`

<h1>Register</h1>

<form action="register" method="post">

<label>Username <input name="u" /></label>

<label>Password <input name="p" type="password" /></label>

<input type="submit" />

</form>

`)

})

// Process registration form

app.post('/register', async (req, res) => {

const { u, p } = req.body // username, password

try {

db.prepare(

'INSERT INTO users (username, password) VALUES (?, ?)'

).run(

u, await argon2.hash(p, {

hashLength: 8, // 8 bytes = 64 bits

saltLength: 8, // 8 bytes = 64 bits

secret: process.env.PEPPER // 128 bits

})

)

res.send('Registration successful')

} catch {

res.send('Username already exists')

}

})

app.listen(3000)

Save the above code in a file called auth.mjs. You can then run the code using:

$ node auth.mjs

Note that for production use you must configure your webserver to act as an https reverse proxy so that the connection is secure. If you do not, any usernames and passwords will be visible to attackers on the network.

Visit [http://localhost:3000/register](http://localhost:3000/register)

After registering you can view the contents of the database using:

$ sqlite3 users.db .dump

Look for the line that looks similar to this:

INSERT INTO users VALUES('a','$argon2id$v=19$m=65536,t=1,p=1$nQXrIgvV7K8$hpL1ZR7iHmA');

The hash returned by the argon2 npm package is of the form:

$id$param1=value1[,param2=value2,...]$salt$hash

This is the PHC’s standardised hash result format. It includes the algorithm used, the algorithm’s parameters, the salt and the hash.

It is good to store the algorithm and its parameters also in case we want to change these at a later point. In that case we won’t have to upgrade all the accounts at once. We can also easily fine tune and increase the memory and computational complexity of the encryption algorithm to account for increases in attackers’ computational power and memory resources over time. In this case we have the following parameters:

Time complexity: 1

Parallelism: 1

Type: argon2id (resistant against GPU and side-channel attacks)

Conclusion

Hashing a user’s strong password with a correctly configured slow hashing algorithm, such as Argon2, and a long, random, unique salt and a long, random pepper provides very strong password protection, even in the worst case of a complete database breach and pepper discovery. Weak passwords, however, will still be vulnerable to discovery by dictionary or brute force attacks, even though their rate of discovery will be dramatically slowed by the well configured slow hashing algorithm:

| Data | Attack | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| User Table | Pepper | Dictionary | Brute Force |

| Secure | Secure | Ineffective | Ineffective |

| Compromised | Secure | Ineffective | Ineffective |

| Secure | Compromised | Ineffective | Ineffective |

| Compromised | Compromised | Effective on weak passwords | Effective on short passwords |

Even with the most secure username/password authentication system in place users should be aware there are other less technical ways for passwords to be stolen such as over-the-shoulder or phishing attacks. At least we can secure the technical aspects of the authentication system so users have one less problem to worry about.

Using the recommended salts and slow hashing algorithm will make lists of usernames and passwords difficult for hackers to generate, even in worst-case data breaches. This helps particularly to reduce the number of cases of attacks where users have re-used passwords amongst different services and consequently we should see less cases of long listings on ’;–have i been pwned?.

Further aspects that need to be delved into in-depth are the minimum lengths of the pepper and the parameters for tuning the Argon2 hashing algorithm.

Further Reading

-

How to securely hash passwords?, https://security.stackexchange.com/questions/211/how-to-securely-hash-passwords

-

Client-Plus-Server Password Hashing as a Potential Way to Improve Security Against Brute Force Attacks without Overloading the Server, “Sergeant Major” Hare, 2015, http://ithare.com/client-plus-server-password-hashing-as-a-potential-way-to-improve-security-against-brute-force-attacks-without-overloading-server

-

Method to Protect Passwords in Databases for Web Applications, Scott Contini, 2014, https://eprint.iacr.org/2015/387.pdf

Jonathan's Coding Journal

Jonathan's Coding Journal